Lebanese hospitality doesn't start with hello—it starts with setting more food on the table than you could possibly eat, then insisting you haven't eaten enough. In Lebanon, the word "mezze" doesn't just describe small plates; it describes a way of life where meals become gatherings, and every gathering becomes a celebration.

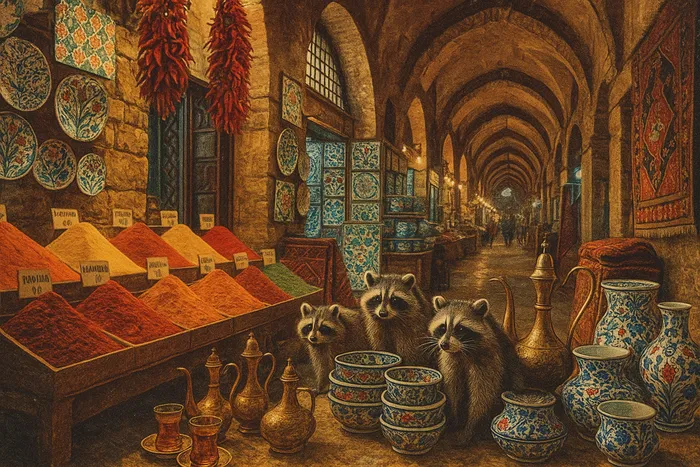

Walking through the souks of Beirut or the mountain villages above the coast, you quickly realize that Lebanese cooking isn't about individual dishes—it's about abundance, variety, and the art of making sure no one leaves hungry or unimpressed.

The Mezze Philosophy

Lebanese mezze culture turns eating into an event. Tables groan under the weight of dozens of small dishes: Baba Ganoush with its smoky depth, Lebanese Tabbouleh bright with parsley and lemon, hummus that's nothing like what you find in supermarkets, and kibbeh shaped with the precision that comes from generations of practice.

But mezze isn't just about the food—it's about time. Lebanese meals stretch for hours, with dishes appearing in waves. Cold mezze first: the dips, salads, and preserved vegetables. Then warm mezze: Lebanese Grilled Halloumi, stuffed grape leaves, and fatayer filled with spinach or cheese. Finally, if you have room, the main dishes.

The genius of mezze is that everyone shares everything. You don't order "your" dish—you order for the table. Conversation flows as freely as the olive oil, and the meal becomes less about consuming food and more about consuming time together.

Markets and Mountain Villages

Beirut's markets pulse with the kind of energy that makes you want to cook immediately and completely. Vendors pile pomegranates like burgundy jewels, their tahini flows like silk, and their za'atar smells like it was mixed that morning (because it probably was).

But the real cooking happens in the mountain villages above the coast, where families still make their own cheese, cure their own olives, and know exactly which hillside produces the best wild thyme for za'atar. These are the kitchens where recipes live in hands rather than books, where measurements come from experience rather than cups, and where the best meals happen when someone's grandmother decides you look too thin.

Essential Lebanese Flavors

Lebanese cooking relies on ingredients that taste like themselves, intensely. Lemons so bright they make you squint. Olive oil that coats your mouth with peppery richness. Sumac that adds tartness without heat. Fresh herbs—parsley, mint, cilantro—used by the handful rather than the pinch.

The spice blends tell stories: za'atar with its wild thyme and sesame, baharat with its warm seven-spice complexity, and dukkah that adds crunch and nuttiness to everything it touches. These aren't just seasonings—they're flavor signatures that make Lebanese food unmistakably itself.

Techniques Worth Learning

Lebanese cooks have mastered the art of coaxing maximum flavor from simple ingredients. They know that good hummus starts with dried chickpeas soaked overnight, not canned ones. They understand that tabbouleh should be more herbs than bulgur, and that the key to perfect Baba Ganoush is charring the eggplant until the skin is completely black.

Watch a Lebanese cook stuff grape leaves (warak enab) and you'll see precision that comes from muscle memory. The rice filling gets seasoned with cinnamon and allspice, rolled tight enough to hold together but not so tight that the rice can't expand, then simmered with lemon juice and olive oil until tender.

Street Food and Home Cooking

Lebanese street food brings the flavors of home cooking to busy streets. Manakish—flatbread topped with za'atar and olive oil—gets eaten hot from the oven for breakfast. Shawarma wraps marry perfectly spiced meat with garlic sauce and pickles. Lahmacun spreads spiced lamb mixture on thin dough, then gets rolled with fresh vegetables and eaten by hand.

But the real magic happens in Lebanese homes, where cooking becomes a communal activity. Family members gather to stuff kibbeh, roll grape leaves, or shape ma'amoul cookies filled with dates or nuts. These aren't just cooking sessions—they're cultural transmission, where techniques and stories get passed down along with recipes.

Cedar Country Traditions

Lebanon's mountain regions, dotted with ancient cedar trees, have their own food traditions. Here, mountain cheeses like ackawi and kashkaval get paired with honey and walnuts. Wild herbs gathered from hillsides become tea or get preserved in olive oil. And the altitude creates perfect conditions for drying fruits and making rose water and orange blossom water that perfume both savory and sweet dishes.

The tradition of preserving—whether it's pickling turnips in brilliant pink brine, packing cheese in olive oil, or drying mint and za'atar for winter—reflects Lebanon's position as a crossroads. These techniques allowed flavors to travel and survive, creating a cuisine that's both deeply rooted and surprisingly diverse.

Modern Lebanese Cooking

Today's Lebanese cooks honor tradition while embracing creativity. They might serve traditional hummus alongside roasted cauliflower with tahini, or present kibbeh as elegant canapes instead of rustic footballs. The flavors remain authentically Lebanese, but the presentations adapt to modern life.

In restaurants from Beirut to Brooklyn, Lebanese chefs are rediscovering forgotten dishes and techniques, proving that Lebanese cuisine has depth far beyond the mezze that made it famous internationally. But even the most innovative Lebanese cooking returns to the same principle: food is love, and love is best shared around a table crowded with dishes and surrounded by people you care about.

The Lebanese approach to cooking and eating offers something essential: the understanding that a meal is never just fuel, but always an opportunity to take care of each other. In a world that often feels hurried and disconnected, Lebanese mezze culture provides a model for slowing down, sharing more, and turning every meal into a small celebration.